Margaret Urwin (née Kelly) has worked with Justice for the Forgotten, the organisation representing the families and survivors of the Dublin and Monaghan bombings, since 1993 and, for more than a decade, with the families of the victims of other cross-Border bombings. Justice for the Forgotten affiliated with the Pat Finucane Centre in December 2010.

TURNING A BLIND EYE

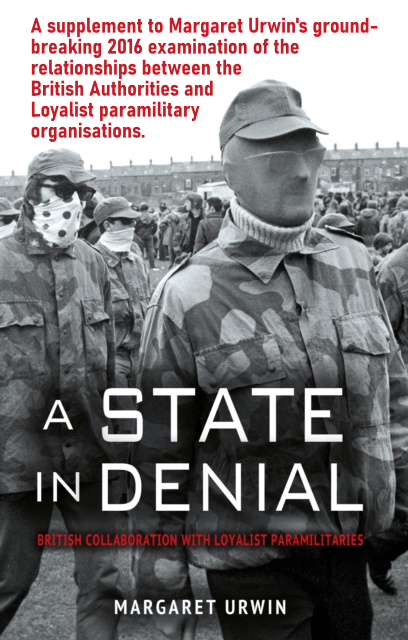

A State in Denial was published by Mercier Press in 2016 in which the story of the British State and its forces and their relationship with loyalist paramilitaries in the 1970s and early 1980s, was told. This paper explores new information that has come to light mainly through recently-declassified official documents in the UK National Archives, Kew, but also through recently-published reports of the Police Ombudsman for Northern Ireland (PONI).

The publication recounted how a policy decision was taken to exclude loyalists from internment in August 1971 which continued for 18 months and how a special ‘Arrest policy for Protestants’ ensured that it was enforced. Loyalist vigilantes were allowed to ‘assist’ the security forces and a blind eye was turned to UDA marchers wearing uniforms illegally and carrying cudgels. Woefully inadequate vetting of UDR applicants resulted in numerous loyalist raids on UDR armouries throughout the conflict which, especially in the early years, was the only source of modern weaponry for loyalist paramilitaries.[1]

A State in Denial also noted that, in the early 1970s at least, joint membership of the UDA and the UDR was permitted. Tuzo, during the first IRA ceasefire in 1972, devised an offensive plan to deal with the IRA should the ceasefire break down. This included a suggestion that ‘Protestant areas could be entirely secured by a combination of UDA, Orange Volunteers and RUC’ and that it might even be necessary ‘to turn a blind eye to UDA arms when confined to their own areas.’[2]

The so-called Ulster Freedom Fighters (UFF) emerged on 9 June 1973, which was no more than a nom de guerre used by the UDA when it carried out sectarian murders. Despite its knowledge that the UFF was not a separate organisation, the British authorities maintained this charade for two decades. Only 10 days after its emergence, an Information Policy Unit (IPU) meeting on 19 June noted that ‘the UFF should not be treated as being separate from the UDA.’[3] Also, in a note on Protestant extremist organisations in late 1973, it was noted that the UFF was ‘a flag of convenience’ for the UDA.[4] An internal NIO paper dated 29 July 1975 noted that ‘the UFF and The Young Militants are pseudonyms adopted by the UDA to maintain their respectable front.’[5] In September 1976, ‘A Guide to Paramilitary and associated organisations’ observed that the UFF was ‘a fictitious organisation.’ [6]

LYING TO THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION OF HUMAN RIGHTS (ECHR)

In its December 1971 application to the ECHR, the Irish Government claimed that the UK had violated a number of the convention rights in Northern Ireland. Included in the complaint was that breaches of Articles 5 (right to liberty) and 6 (right to a fair trial) had occurred, and that the arrests, detaining and interning of persons was carried out with discrimination on the grounds of political opinion and this breached Article 14. The three witnesses who gave evidence to the Commission on behalf of the British Government in this regard on 20 February 1975 in London were General Harold Craufurd Tuzo – Director of Operations and General Officer Commanding (GOC) Northern Ireland (March 1971-February 1973); Sir Robert Edward Graham Shillington – Chief Constable of the RUC (November 1970-October 1973) and Philip John Woodfield – deputy Under-Secretary of State for Northern Ireland. All three provided misleading information to an international commission. They lied about the extent of sectarian bombings being perpetrated by loyalists; they lied about the UFF being a separate organisation from the UDA; they lied about the so-called unstructured, undisciplined, amorphous nature of the main loyalist organisations when they were well aware of their formal structures; they lied about loyalists being ‘more amenable to the normal criminal system’; they lied about ‘members of organisations’ being involved in terrorist acts but not the organisations themselves; they lied about ‘Protestant organisations’ being dormant between 1969 and the introduction of direct rule. Most significantly, they lied about the UDA’s involvement in sectarian killings.

In November 1973, in order to maintain this deception, the British Government proscribed the non-existent UFF along with the Red Hand Commando.

DE-PROSCRIPTION OF ULSTER VOLUNTEER FORCE

Both the UVF and Sinn Féin were de-proscribed in May 1974. The net effect of the UVF’s de-proscription meant that both of the main loyalist paramilitary organisations were now legal and the official British view was that neither organisation was involved in violence. The amendment to the Northern Ireland (Emergency Provisions) Act 1973 was moved in the House of Commons on 14 May and by the House of Lords the following day. The Ulster Workers’ Council (UWC) strike (in which the UDA and UVF were major players) began on 15 May and, two days later, the newly-legal UVF bombed Dublin and Monaghan, resulting in 34 deaths. Despite the bombings, the de-proscription legislation was allowed to come into effect on 23 May.

The organisation remained legal until 4 October 1975 despite many subsequent attacks including the Miami Showband murders on 31 July 1975, which were clearly perpetrated by members of the UVF acting jointly with UDR members. In an internal memo, dated 17 September 1975, David J. Wyatt, MI6,[7] noted that a decision had been taken not to re-proscribe the UVF but he suggested cynically that ‘we should keep it up our sleeves until we decide to take…real measures in the field against Republicans; we could then play this card…in the even-handedness game[8].’ The British Government’s hand was, however, forced when the UVF went on a murder rampage on 2 October killing eight Catholics and losing four of its own members in a premature explosion. It was re-proscribed under the emergency instrument and, from then on, the UVF remained proscribed and, to a large extent, fell from favour with the authorities, unlike the UDA.

RUC FAILURE TO INVESTIGATE LOYALIST MURDERS

In the early 1970s regular meetings were held by the Northern Ireland Office (NIO) with both the UVF and the UDA but more frequently with the UDA, particularly in 1975, during the second IRA ceasefire.

British officials massaged figures relating to loyalist sectarian murders in meetings with Cardinal Conway and the Irish Foreign Minister, Garrett FitzGerald. At one such meeting, Secretary of State Merlyn Rees described loyalist murderers as ‘individual Protestant travelling gunmen.’[9]

There was an acute awareness of RUC failures to investigate these murders. Frank Cooper, the Secretary of State’s Private Secretary, observed that the RUC was hampered through shortage of CID staff; fears about its own safety if it pressed its inquiries too vigorously in hard loyalist areas; the inadequate degree of dissemination of information from Special Branch to CID; and the greater constraints which the courts and the DPP in Northern Ireland placed on the police in terms of the preparation and treatment of offenders. This is official recognition at the highest level in the Northern Ireland Office (NIO) that the RUC was unable, or perhaps unwilling, to pursue investigations in loyalist areas and confirmation that information was not shared sufficiently by Special Branch with CID.[10]

At a meeting in 1975 with John McColgan, a Department of Foreign Affairs official, the Rev (later Canon) William Arlow, the Church of Ireland minister who had been a driving force behind the Feakle talks with the IRA in late 1974, told him of his concern about the close relationship between the NIO and the UDA. He suggested that there was ‘an informal pact between the NIO and the UDA and that the British were giving considerable amounts of money to UDA welfare organisations.[11]

In the year following the INLA murder of Airey Neave, the shadow secretary of state for Northern Ireland, on 30 March 1979, the UDA began to target and kill high-profile republicans. Most of the victims, but not all, were believed to have had some connection to the IRSP, the political wing associated with the INLA. The victims were also involved in the H-Blocks campaign. John Turnly, Miriam Daly, Ronnie Bunting and Noel Lyttle were killed while Bernadette McAliskey and her husband, Michael, were lucky to survive a shooting attack. Rodney McCormick was killed in the mistaken belief that he was a member of the INLA. Eventually, UDA members Robert and Eric McConnell and William McClelland were convicted of both John Turnly’s and Rodney McCormick’s murders. At the end of the trial, Robert McConnell claimed to have been working for the SAS. He told the court that information concerning Turnly and others was fed to him by the British intelligence services.[12] During the trial the term ‘UFF’ was never mentioned, nor was the fact that one of the accused had served in both the UDR[13] and the prison service[14], the latter being highly relevant given John Turnly’s involvement in the H-Blocks campaign. McClelland’s membership of the prison service was also very significant in that the Historical Enquiries Team (HET) confirmed that the gun used to kill Rodney McCormick was also linked to the attempted murder of a Catholic prison officer in Newtownabbey in May 1980.

Suspicions of state involvement were fuelled by a detective’s admission during the trial regarding ‘sensitive information’ he had received during interviews with Eric McConnell. The Detective Chief Inspector in charge of the case considered the information so sensitive he told the detective to destroy his interview notes and to re-write them.[15] These interventions raise serious questions about the British authorities’ relationship with the UDA.

RESISTANCE TO UDA PROSCRIPTION IN THE 1980S

In the wake of these sectarian murders and attempted murders, there were many calls for the UDA’s proscription, including from the SDLP and the Alliance Party. The US Government also expressed unease. The British Foreign Secretary, Lord Carrington, advised his ambassador in Washington of ‘the line to take’ in a telegram dated 4 November 1980 – a ‘line’ that was utterly disingenuous. The telegram noted as follows:

The UDA have not claimed responsibility for these killings. The police investigate all acts of violence with a view to bringing the perpetrators to justice irrespective of religion or political or paramilitary affiliation. There have been many convictions for murder in Northern Ireland where those convicted are known to have had ‘Loyalist’ affiliations, but the UDA as an organisation has never admitted to the use of terrorist violence to achieve its aims…

Not for disclosure

The three men charged with the murder of John Turnly are believed by the police to be members of the Ulster Freedom Fighters (the unadmitted terrorist wing of the UDA). It is believed that all the murders mentioned are the work of either the UVF or the UFF. In general, the Government prefers to use its powers to proscribe named organisations as sparingly as possible. Thus both the PSF and the IRSP remain legal organisations, in spite of their close links with PIRA and INLA respectively. The relationship between the UDA and the UFF is not dissimilar.[16]

This telegram is breath-taking in its mendaciousness. Carrington is being deceitful even with his own ambassador.

The recording of a sentence in an internal memo of 5 June 1981 is quite unsettling – the Secretary of State had noted two days previously that ‘proscription would deprive them [the NIO] of the access they presently had to those members of the UDA who were actively involved in terrorism’.[17]

There were recoveries of arms and ammunition from UDA Headquarters on 26 July 1977; on 26 May 1981 and again on 14 April 1982. In relation to the third arms recovery, the police found 150 identifiable fingerprints of the accused men who included Andy Tyrie and John McMichael. Tyrie and McMichael were given bail despite the prosecution’s claim that the fingerprints of both men had been found on confidential documents. Prosecuting counsel told the court that thousands of documents had been seized in the three raids. Charges against five of the men – all except Andy Tyrie – were withdrawn by the DPP. Tyrie remained on continuing bail and, incredibly, his case did not come to trial until 25 February 1986. It took just one hour for him to be tried and acquitted of the charge of possessing documents despite his fingerprints being found on them.[18]

A closed NIO file: CJ4/2841 – UDA: Meetings and contacts with UDA leadership (1976-79) is held in the National Archives, Kew. This, despite the fact it was claimed that no meetings had taken place with the UDA after Roy Mason was appointed as Secretary of State for Northern Ireland in 1976. This file originally had an opening date of 2052. An FOI for the file was lodged in 2018, which was rejected. The file was reviewed at that time, the upshot of which is that the file is now closed for 100 years.

At a meeting with the SDLP on 16 February 1981, John Hume complained that the Chief Constable, in his annual report for 1979, had made no mention of the UDA in the context of terrorism, to which Secretary of State, Humphrey Atkins, made the astonishing reply that the difference between the UDA and PIRA was that ‘the latter quite frequently admits responsibility for acts of terrorism whereas the UDA do not.’[19]

In another internal memo of 22 September 1981, Colin Davenport of the Law and Order Division of the NIO wrote: ‘In terms of the politics of proscription [of the UDA], we have always regarded the existence of such denials as more important than their accuracy.’ This illustrates the cynicism at the heart of the British Government towards the UDA.

Again, in 1985, pressure was being brought to bear by US Senators about the status of the UDA. A resolution calling for the organisation’s proscription was submitted to the US Senate by Senators Dodd, Moynihan and Kennedy in March. Nigel Sheinwald from the Political Section of Washington’s British Embassy sought a briefing from the NIO as to why the UDA was not proscribed.

In a lengthy briefing on 11 April, NIO official Derek Hill, while actually acknowledging that it was loyalist violence which started the Troubles and that, at least in 1975, they constituted the bulk of terrorist activity, he insisted that ‘the UDA has never been primarily and actively concerned in terrorism’. Some of its members, he opined, had committed acts of terrorism during the 1970s (no mention of the 1980s) but they did so as members of the proscribed UFF, not as UDA members. This was the mantra behind which ministers and officials would hide in the following years.

In response to the briefing, Howard Beattie, British Information Services in New York,[20] expressed concern about a sentence in the briefing – ‘that the UDA did not commit acts of terrorism during the 1970s.’ He wondered how that squared with the fact that, under Special Category arrangements, there was a UDA classification and there was still a UDA compound. He wrote that one of the elements of being granted ‘Special Category Status’ was that the organisations ‘laid claim’ to individuals who had committed crimes in their name.

Derek Hill’s reply, drafted for him by SL Rickard, Law and Order Division of the NIO, is a masterpiece in verbal gymnastics and deserves to be quoted in full. The labyrinthine machinations in which these officials engaged are jaw-dropping:

The statement is correct in so far as those UDA members who committed acts of terrorism claimed publicly that those acts were done on the authority of the UFF, not of the UDA. If pushed to explain why these self-same terrorists, when committed to prison, organise themselves on a UDA rather than UFF basis, I would say that there is not necessarily a direct connection between the authority which terrorists claim for their acts of violence and the way in which they subsequently organised themselves in prison. If…the UDA is primarily a social and secondarily a political organisation then it is only natural that its members, when committed to prison, should organise themselves so as to stick together. It does not follow that the acts of terrorism committed by those prisoners were necessarily authorised by the UDA leadership or (more to the point) that the organisation as a whole was (or remains) primarily engaged in terrorist activity. The point about the existence of the UDA compound is that it exposes what is in fact a close relationship between the UFF and the UDA. Outside the prison, one is a subset of the other; inside, they merge.[21]

Rickard’s covering memo sent along with the draft, dated 1 May 1985, stated that ‘It is possible by nifty semantics to stand over the statement’ in the draft. However, he observed, (in a rare moment of candour), the point exposed by Mr Beattie’s letter ‘is that the relationship between the UFF and the UDA is a good deal closer than the paper admits; UFF is no more than a nom de guerre and some (if admittedly not all) UFF terrorist activity is/was directed by the UDA leadership’.[22]

SPECIAL RELATIONSHIPS

Recently discovered documents from 1973 and 1974 reinforce our knowledge of the special relationship between British authorities and loyalist paramilitaries.

There were special rules as to how ‘Protestant extremists’ were to be treated. Operations against them had to be governed by a number of principles which included the following:

- They must not generally be conducted at the expense of operations against the IRA

- They should be designed to avoid provoking a Protestant reaction or escalation, in particular a UDA [surely UDR is meant here] call-out or generation of moderate Protestant opposition

- Protestant terrorism should ideally be prevented or at least stifled quickly in order to avoid a resurgence of support for the OIRA and PIRA by the RC community. This might entail a pre-emptive arrest operation

- Arrests should generally be made only in the case of evidence sufficient to ensure a criminal prosecution or, failing that, the signing of an ICO; searches in Protestant areas should only be made on good intelligence.[23]

Another very interesting document chimes with the special arrangements set out above. It provides an interesting insight into how British Army regiments on tours of duty in Northern Ireland were instructed in the outworking of these arrangements and the sensitivities that should be employed in dealing with loyalists. It proves that this practice was institutionalised.[24]

(It should be noted that loyalist paramilitaries were usually described as ‘extremist Protestants’ or, simply ‘Protestants’ by the British authorities).

In a post-tour report of 1 Royal Anglian Regiment, which took place from September to December 1974, there is an extraordinary account under the heading of ‘Intelligence Matters’. It is noted:

Peculiar Problems of handling Protestant

9. Although dealing with Protestants in the Province is the third priority behind the defeat of the PIRA and the militant elements of the OIRA, these operations are still necessary. However, all actions against them are particularly sensitive.

Problems arise because:

- Protestants are in the large majority

- The security forces are basically Protestant (and loyal)

- Many members of extremist organisations are highly respected members of the population, which backs their Loyalist ideals and turns a blind eye to militant activities

- For reasons of security it is necessary to restrict sensitive information:

- Within the RUC itself

- Within the UDR

- Within the Army

which can reduce briefing time to a minimum and even preclude the use of some agencies in anti-Protestant Ops [Operations] and Int [Intelligence] tasks.

- Extreme Protestants invariably react vigorously against any suspicion of pressure or extra attention. They are quick to ‘set up’ SF [security forces] and bring pressure to bear.

- Many operations require highly specialised troops who, because they are in short supply, are occasionally not available thus causing postponement or cancellation of important and sensitive tasks.

10. For all these reasons, operations against Protestant extremists must be planned with great care, and those soldiers who are involved must be very sensitive to the political as well as the military implications of their actions.[25]

It is clear from those instructions that ‘Protestants’ or, more correctly, ‘Loyalists’ were to be treated with kid gloves by the security forces. 1 Royal Anglian was made aware that it was an accepted fact that many loyalist paramilitaries were ‘highly respected members of the population’ – a population that turned a blind eye to their violent actions. Shockingly, it was taken for granted that some members of the security forces could not be trusted and, therefore, it was necessary to restrict sensitive information within the RUC, the UDR and the Army. Because of this lack of trust, some agencies had to be excluded from ‘anti-Protestant’ and ‘Int’ tasks entirely. It was deemed necessary to use ‘highly specialised troops’ in such operations, but if they were not available, these operations were either postponed or cancelled, thus possibly missing opportunities to solve crimes, including murder. This practice showed complete disdain for the rule of law.[26]

GUN LICENCES FOR UDA MEMBERS

One of our new discoveries is that the RUC, in consultation with the NIO, was willing to provide and renew gun licences for UDA leaders. It is worth bearing in mind that, by the end of 1972, the UDA had killed 80 people.

On 14 December 1972, the Chief Constable, Graham Shillington, wrote to Jack Howard-Drake, NIO, reminding him that the question of the issue of firearms certificates to members of the UDA enabling them to hold weapons for their personal protection had been discussed on more than one occasion at Secretary of State’s meetings.[27]

He attached a list ‘giving particulars of 12 members of the UDA and kindred organisations’ – the list is redacted – who had been issued with firearms certificates for their personal protection. Some of them were due for renewal at the end of the month. He noted that his powers to revoke a licence could be applicable only if:

- The person had been convicted of a criminal offence;

- He was of intemperate habits;

- He was of unsound mind.

- He was otherwise unfitted to be entrusted with firearms.

These conditions, the Chief Constable suggested, would cause ‘considerable difficulty in justifying the revocations of any of the certificates already issued.’ He requested that the matter be brought to Secretary of State’s attention ‘in view of political repercussions which might arise if any of these certificates are revoked’.[28]

Jack Howard-Drake forwarded the Chief Constable’s letter to Sir William Nield on 5 December and also copied it to Frank Steele, a member of MI6,[29] who, at that time, was attached to the NIO. In a covering note, Howard-Drake expressed scepticism about the police being under any obligation to renew certificates indefinitely.[30]

On 19 December, Frank Steele replied to the Chief Constable saying that UDA leaders would argue that they were at risk of being shot, ‘as demonstrated by the recent murder of Ernie Elliot’.[31] (In fact, Elliot was killed by his own organisation in Sandy Row).[32]

Steele’s view was that, ‘unless we have firm and clear grounds for the revocation of these firearms, we should not revoke them in the present situation because of the political and security repercussions which revocation would cause. [Emphasis added]. Steele went on to say that, in a telephone call with UDA leader, Tommy Herron, a few days previously, he mentioned that his and Jim Anderson’s were up for review at the end of the month.[33]

There is a note in the margin which reads: ‘As you know S of S decided to accept the advice that the licences could not in practice, be revoked at this stage’.[34]

So, a political decision was made to continue to licence certain UDA members to carry legal weapons.

Ironically, like Elliot, Tommy Herron was assassinated by his own organisation on 16 September 1973.[35]

We don’t know if Andy Tyrie, leader of the UDA, held a gun licence at that time. However, it was noted in A State in Denial that, more than two years later, Tyrie held a clandestine meeting with James Allan, NIO, on 10 March 1975 at which he requested that Allan assist him in procuring a firearms certificate. Allan suggested that it was ‘just possible’ that his bodyguard might be able to obtain one if he was not a member of an extremist organisation. Allan, in a telephone call sometime later, suggested to Tyrie that the bodyguard should apply immediately for the weapon’s certificate indicating that he would check as to which police station the man should apply. Allan, in a memo dated 24 March to a person whose name is redacted, believed that this was ‘a useful precedent in the context of other very delicate matters of which you are aware.’[36] We are not told what these ‘delicate matters’ were.

ATTITUDES TO THE RULE OF LAW WITHIN THE TOP ECHELONS OF THE RUC

In early June 1981, NIO official PWJ Buxton, sent a memo to the Private Secretary of the Secretary of State in which he disclosed that the Chief Constable, John Hermon, had threatened, if the government decided to proceed with the proscription of the UDA, that it could not count upon his support, and he hoped to be given the chance to state his views before a final decision was taken, preferably at a meeting with the Secretary of State. This suggests the Chief Constable was exerting undue influence on government policy.[37]

In the New Year of 1982 the Chief Constable was expressing concern about the disillusionment and isolation of the UDA. He blamed the government for failing to recognise it as a ‘legitimate political organisation.’[38] Hermon claimed that the UDA had now ‘decided to adopt a more violent tactic by assassinating 15 leading members of the PIRA.’ He reported, rather chillingly, that the police might be unable to prevent these murders as that would compromise his source.[39]

The higher echelons of the RUC appear to have had a rather ambiguous relationship with the rule of law in general.[40]

BRIAN NELSON’S RECRUITMENT

In updating the story of the relationship between the British State and loyalist paramilitaries, it would be remiss of us not to include the central role of the agent, Brian Nelson, even though much of the information comes from the De Silva report into the murder of Pat Finucane and Nelson’s own journal. His story consolidates Britain’s secret war in Northern Ireland, confirming complicity with murder and lying about it. The Nelson saga is a sordid tale of collusion at a high level between the British Army / RUC Special Branch and the UDA.

From October 1965 until February 1970, Nelson served in the British Army’s Blackwatch Regiment. He was discharged on grounds of mental instability. He returned to Belfast and joined the UDA.[41]

In March 1973, Nelson abducted, brutally beat and tortured a partially-sighted Catholic, Gerard Higgins. Nelson and two accomplices were caught red-handed by members of the Coldstream Guards removing Higgins from their ‘romper room’ to, most likely, his death. They got off lightly – Nelson as ring-leader was sentenced to seven years. His accomplices received, respectively, two years and a suspended sentence.

It is possible that Nelson may have been recruited by the security forces at that time. A contemporary Royal Military Police report suggests this possibility.[42] The RMP author informed his Commanding Officer why the arrest procedure was delayed. On arrival at Springfield Road RUC Station, he met with the 2nd Battalion Coldstream Guards Intelligence Officer. The latter informed him that, before handover to the RUC, he had permission from the Brigade Major, 39th Infantry, to interview each of the three males in custody, providing him with ample time alone with Nelson.[43]

Brian Fitzsimons, Deputy Head of Special Branch (DHSB), claimed in a July 1990 memo that, on release in August 1977, Nelson ‘avoided contact with the UDA and lived quietly.’ That is, until he rang the Intelligence Section in Lisburn Garrison on 4 May 1984 to offer his services. He was met by personnel from the Force Research Unit (FRU).[44] It is an open question as to whether Nelson had worked for the security forces beforehand.

Despite clear evidence of mental instability and sectarian brutality, FRU tasked Nelson to re-join the UDA. He was soon appointed Intelligence Officer for west Belfast.

NELSON IN SOUTH AFRICA

In the journal he wrote after his arrest, which the author has seen, Nelson claimed that, in May 1985, he was asked to go to South Africa by Andy Tyrie, John McMichael and Tommy Lyttle. He was told that the UDA had been searching for years for someone to supply the organisation with weapons and, at last, they had found someone in South Africa. Nelson was requested to negotiate an arrangement with the arms dealer, find out the cost and the method of exportation. The leadership had met previously with a man who was a native of Armagh but now living in Durban. This man had sought out and found an arms dealer who was willing to supply the UDA. Nelson was asked to come up with a possible solution to the difficulty of importing the arms from Europe and a meeting was arranged for him with a shipping clerk employed by Harland and Wolff to learn about import formalities. It was decided that the arms should be shipped to Rotterdam, the largest container terminal in Europe.

Nelson informed his FRU handler, Mick, about his forthcoming trip and, at his following debriefing, he was told that permission for him to go had gone all the way to the top – ‘all the way to Maggie.’ Nelson believed that to be an exaggeration.

Nelson reported that Tyrie took him to a travel agency in Connswater where his tickets were booked and Tyrie agreed to pay the bill. He also gave Nelson money for his expenses. Nelson flew to London on 7 June on the pretext that he was attending a Barry MGuigan fight the following night and let it be known that he was then going on to visit relatives in Liverpool afterwards. He flew to Johannesburg and thence to Durban. He met with the Armagh man who impressed Nelson with his sincerity and honesty and ‘his sense of patriotic duty to Ulster’ and compared the UDA leadership, with the ‘possible exception of McMichael,’ unfavourably with him. This man was Charlie Simpson, a doctor’s son, who had to leave Armagh in a hurry in the 1970s because he was wanted for questioning relating to an offence. He had been an active member of Col. Brush’s Down Orange Welfare (DOW). He emigrated to Africa where he joined the Rhodesian Army’s Selous Scouts.[45] At the time of Nelson’s visit, he was employed in the Ministry of Transport in Durban.

Simpson took Nelson to meet with the arms dealer, a Mr. Millar. The initial order was to obtain weapons and ammunition to the value of £100,000. He was shown the following weapons: the standard-issue assault rife in use with the South African Defence Forces; the standard SMG of Czech design; the Browning Star 9mm automatic pistol and a weapon called the Striker, an automatic shotgun made exclusively in South Africa. Explosives by the ton were also available, as were RPG launchers and limpet mines. Millar claimed to have supplied Iran, Iraq, Israel and China with all sorts of hardware. He said he worked closely with Armscor and produced under patent some of their weapons in his own factory.

On a second visit, Millar told them that, owing to the war in Angola, South Africa had captured and stockpiled a massive assortment of weapons which were for sale at ‘bargain basement’ prices. They agreed the method of payment and Nelson was provided with Millar’s bank details. All transactions were to be conducted through Millar’s agent in Zurich whose name and telephone number were also provided.

During Nelson’s second week in Durban, Simpson mentioned that ‘somebody’ from the Bureau of Information was asking if Nelson could get hold of a Short’s Blowpipe and, if he could, they would be willing to do a trade-off in an arms exchange. It was also suggested that he do a hit on a house in the Rosetta area of Belfast where ANC members, who were students at QUB, were alleged to be living and, it was claimed, were being given bomb-making lessons by the Provisional IRA. Nelson claimed to have been troubled by these requests which, he believed, suggested South African Government involvement in the whole affair.

When he returned he was met by his handler, Mick, in Heathrow Airport where he was debriefed while a member of MI5 went through his luggage. He provided a diary, which he had kept during the trip, to Mick, who pocketed it.

He reported back to the UDA leadership on all that had happened but omitted to mention that he believed the South African Government ‘had a finger in the pie.’ About a month later Lyttle told him the UDA did not have the money to proceed with the importation of the weapons. Nelson had been worried that a shipment might be seized en route and the finger of suspicion would be pointed at him. His new handler, Ronnie, however, had told him that, because of the suspicion a seizure would have aroused, it had been decided to let the first shipment into the country untouched. It would have been carefully monitored, though, as the shipment was being broken down. De Silva utterly rejected this claim and insisted that, whatever the consequences, the shipment would have been seized.[46] De Silva quoted from Nelson’s journal regarding the first shipment being allowed to proceed untouched. However, he omits the next sentence which noted that it would have been carefully monitored.

Nelson, having been offered a good job, left Belfast for Germany in October 1985 and did not return for 19 months. In his journal, he purported to know nothing of the arms shipment in December 1987. He claimed to have learned of the July 1987 bank robbery in Portadown only through media reports and later when he overheard a conversation between two UDA members. (See below). Later again he became aware of Davy Payne being stopped in Portadown and a consignment of weapons being seized in January 1988.

It is uncertain whether a shipment was imported after Nelson’s departure for Germany. While Desmond De Silva was adamant in his 2012 report that there was no shipment, he acknowledged that obtaining weapons was Nelson’s sole purpose and that it was done with the approval of MI5 and FRU.[47] Judge Cory was less certain and stated: ‘Whether the transaction was consummated remains an open question although, in September 1985, Nelson reported to his handlers that the deal fell through due to the inability of the UDA to raise the necessary funds for the purchase.’[48] Cory also claimed that FRU paid Nelson’s expenses.[49]

NELSON’S RE-RECRUITMENT

As noted above, Nelson left Belfast in October 1985 and worked in Germany until mid-1987. He had no sooner settled into his new life before FRU was anxiously trying to re-recruit him, meeting him as early as December 1985. For a time, both FRU and MI5 competed for Nelson’s services. MI5 even considered employing him as an agent.[50]

Nelson was eventually re-recruited by FRU with the blessing of no less than the Army Chief of General Staff and Assistant Head of Intelligence who was a FRU officer. MI5’s Director General was also involved. Nelson was offered a very tempting package – a house was purchased for him and a taxi (designed as a cover for his surveillance activities) costing a total of £7,200, plus £200 per month for his services.[51]

Why was the re-recruitment of Nelson considered necessary at all? The OC of FRU, Col Gordon Kerr, told the Stevens Inquiry:

There was a desperate need for operational intelligence on the Protestant terror groups, who were successfully targeting individuals for assassination…We, in the FRU, decided that if we could persuade Nelson to return… we could reinstate him as Intelligence Officer in the UDA and gain valuable intelligence on UDA targeting.’[52]

That statement does not add up. Killings carried out by the UDA in that period were:

1982: 1 Catholic civilian;

1983: 1 UDA member and 1 Protestant civilian;

1984: 1 Catholic civilian;

1985: 1 Catholic civilian (the year Nelson left Belfast);

1986: 4 Catholics, 1 Protestant and 1 UDA member (while Nelson was in Germany);

1987: 11 people killed, nine of them after Nelson’s return[53]

A telegram dated 21 May 1987 confirmed that ‘[Nelson] is now established in UDA HQ.’[54]

In 1988, the UDA’s killing rate increased to 12 people and six were killed in 1989, all during Nelson’s term of employment.[55]

FRU tasked Nelson to focus his targeting on ‘known PIRA activists.’ Col Gordon Kerr explained his rather dubious rationale for this in his October 1990 statement to Stevens:

We carefully developed Nelson’s case…with SB with the aim of making him Chief IO for the UDA. By getting him into that position, FRU and SB reasoned that we could persuade the UDA to centralise their targeting through Nelson…on known PIRA activists who… were far harder targets. In this way, we could get advance warning of planned attacks, could stop the ad hoc targeting of Catholics and could exploit the information more easily because the harder PIRA targets demanded much more reconnaissance and planning and this gave the RUC time to prepare counter measures. In the event, this concentrated targeting also resulted in far fewer attacks, because despite a great deal of reconnaissance, PIRA targets often proved too difficult.[56]

A certain inescapable fact, in De Silva’s view, was that Nelson’s return from Germany – for which FRU was responsible – increased the UDA’s ‘military’ capacity to target and attack supposedly ‘legitimate’ republican figures.

De Silva insisted that neither Nelson nor FRU had any involvement in the arms shipment via Lebanon in December 1987. He placed the bulk of responsibility on Ulster Resistance. This chimes with Nelson’s account in his journal. Ian Cobain, writing in The Guardian, however,quoted an Armscor source that ‘when arrangements were being made for the shipment of the arms from Lebanon, it had to be agreed by John McMichael and his intelligence officer, Brian Nelson.’[57]

As can be observed throughout De Silva’s report, FRU claimed they passed on Nelson’s information on targeting individuals to RUC Special Branch so that their murders could be stopped. Special Branch (SB), on the other hand, claimed that FRU often failed to pass information to enable them to take action as in the Gerard Slane case noted below.

In a declassified NIO file, authorities expressed concern about claims being taken by the widows of Gerard Slane and Terence McDaid, targeted by Nelson and murdered by the UDA. It was noted that ‘it will be impossible for the MoD to deny that Nelson was in their employment and had passed to them clear evidence of Slane and McDaid being targeted’. They worried that a court could find that the security authorities were at least negligent in continuing to permit Nelson’s involvement in conspiracies to commit murder and failing to act on his information to prevent their deaths, or worse, that they conspired in the killings.[58] De Silva regarded the Slane case as the most serious example of FRU failing to pass on important intelligence to RUC SB prior to a UDA attack taking place.[59]

Another case was the attempted murder of Sinn Féin’s Alex Maskey. Nelson told his handler of his near success in killing Maskey on a previous Sunday, missing him by about 20 seconds. The handler, without hesitation, confirmed Maskey’s car registration number, thus facilitating further possible attacks. De Silva found it ‘difficult to conceive of a clearer example of FRU…being prepared to assist the UDA with their targeting…rather than action to save lives.’[60]

Nelson also disseminated targeting material to the proscribed UVF, over whom his handler had no control. The handler wrote on 7 April 1989:

Nelson feels that if the UDA are not going to act then it is better that the UVF do it than no one. Although the UVF are not particular about their targets they appear to be more aggressive. If this is successful it will enhance Nelson’s standing with L/28 [a UDA leader], particularly if the UVF carry out an attack on one of the targets for which Nelson supplied the information. [61]

It seems to have been clearly understood that the information could assist the UVF in carrying out the attacks. There is no suggestion that it would be used to save lives.

De Silva insisted that the strongest evidence of FRU handlers passing information to Nelson is to be found in their own documentary records. For example, when they provided him with registration numbers of five cars, Nelson was advised to tell UDA leader, Tommy Lyttle, he had obtained them on a drive past Conway Mill. One of those vehicles belonged to IRA member, Brendan Hughes.[62]

In his journal, Nelson claimed that a FRU agent known as ‘The Boss’ had suggested to him that the UDA should consider undertaking a bombing campaign ‘down South across the border.’ He allegedly put it to Nelson that such a campaign should be conducted on commercial targets that would cause maximum economic damage ‘because of the present state of Eire’s [sic] economy. This would bring pressure to bear on the ‘Eire [sic] Government’ to have a re-think on their extradition policy. He suggested the ‘oil terminal outside Cork’ as a suitable target. Nelson claimed that those who attended this de-briefing, as well as ‘The Boss,’ were handlers Mags, Martin or Andy or both ‘at one stage or another’ but that Mags was present throughout. Nelson approached McMichael with the suggestion who was ‘totally taken’ with the idea. He sent someone to do a recce and take photographs which were given to Nelson who recorded that he could only assume that, when McMichael was killed in December 1987, the bombing project died with him. When he was later questioned by the Stevens team about the photographs, Nelson said he led those questioning him to believe that the idea had originated with McMichael but gave no reason for changing his story.

UDR AND RUC WORKING WITH LOYALIST ORGANISATIONS

The Stevens investigation exposed serious problems inherent in the UDR vetting system, which, from our own research, we know existed from the very formation of the regiment. Stevens found 1,350 adverse RUC vetting reports on individuals seeking to join the UDR during 1988-9. Despite that, 351 of these were enlisted[63]. Of 210 loyalists arrested by Stevens, all but three were working for one or other State agency,[64] further evidence that loyalist paramilitaries acted as a deniable arm of the state.

Very significant assistance was provided by members of the security forces to loyalists. In 1985 alone, of thousands of items of intelligence material held by the UDA, 85 per cent was drawn from UDR and RUC records. De Silva listed 270 instances of security force leaks to the UDA between January 1987 and September 1989.[65]

Raids on UDR armouries, many of which were recounted in a State in Denial, were continuing as late as 1987. In February, two UDR members from the Coleraine base approached the iniquitous Davy Payne, the UDA’s north Belfast Commander and also the UDA’s procurement officer, and suggested he organise a raid at their base.[66] Eddie Sayers, mid-Ulster UDA Brigade Commander, was offered a ‘share’ but turned it down. Some days before the planned raid, two of Payne’s north Belfast associates were picked up in connection with fire-bomb attacks on Dublin shops. Despite the likelihood that these associates would be ‘singing’ in police custody about Payne’s current operations, he not only went ahead with organising the raid but participated in it personally.

On the night of 22 February, he and three others arrived at the base. He was driving his own car and his colleagues had a van. The two UDR men met them at the entrance and took all but the driver inside in the boot of a UDR vehicle. When the driver of the van (waiting outside) suddenly panicked and drove off, the others had to load the stolen weapons into a UDR vehicle parked inside the base. Payne drove off in his own car while his colleagues followed about half a mile behind in the UDR van. At about 4.15am, not far from the base, Payne was stopped by traffic police. They established his identity and his destination (a relative’s house in Glengormley) and then let him procced. A few minutes later, they stopped the UDR van, discovered the weapons and arrested the two UDA men. Payne was subsequently arrested at the house in Glengormley; the UDR accomplices were also arrested. Payne was later released as, it was claimed, there was no hard evidence to link him to the raid.[67]

In September 1989, according to De Silva, the Head of Assessments Group wrote to the Director & Coordinator of Intelligence as follows:

Our researches suggest that RUC links are as extensive as the UDRs…UDA/UDR links are significant. Given the differing sizes and nature of the UDA and UVF (the latter being a proscribed organisation) we would expect there… to be more scope for contact between the security forces and the UDA than the UVF. [68]

In December 1988, MI5 and RUC SB learnt of an intended UDA break-in to a UDR base in County Down so as to obtain intelligence on individuals ‘allegedly connected to republican terrorism.’ Nelson was able to provide some intelligence prior to the UDA accessing the base and, after the break-in, he provided detailed intelligence to his handlers.[69] De Silva noted that a decision was taken by the RUC not to seek to prevent the UDA from obtaining the UDR intelligence material. Brian Fitzsimons, Deputy Head of Special Branch (DHSB) took a very nonchalant view, advising that: ‘since the UDA already had lots of this stuff anyway’ and that they would find nothing of value, there was little to be gained by trying to prevent it.[70]

In the event, a videotape of a UDR briefing featuring a number of individuals, including Loughlin Maginn, a young Catholic father of four children from Rathfriland, was discovered. FRU recorded that Nelson had viewed the video tape and also noted that the UDR members had offered ‘refuge’ in the local barracks to the UDA team.[71] The UDA targeted a number of individuals featured on the tape but subsequently selected Loughlin Maginn as a target. While Nelson does not appear to have been involved in the targeting of Maginn, he certainly encouraged attacks to be made against those featured on the video tape. It was noted by FRU: ‘Nelson suggested that if no attacks resulted on any of those mentioned on the video tape, the UDR personnel who supplied it would not supply any more.[72] The MoD was greatly alarmed in case this might become public knowledge, noting that ‘this is potential dynamite’ and that ‘the RIR’s [UDR’s] credibility would be severely damaged.[73] This resulted in the UDA killing Maginn in August 1989. The video tape of the UDR briefing was subsequently shown to journalists by the UDA which ultimately prompted the Stevens 1 investigation.[74]

According to McKittrick et al, Loughlin Maginn had been detained by the army and police on a number of occasions over the previous 18 months. He told his wife the police had threatened him with loyalist assassination and security force harassment. He was constantly being stopped and was prosecuted for minor traffic infringements.[75]

Two men, Andrew Browne and Andrew Smith who were full-time serving members of the UDR at the time of Loughlin Maginn’s death, were convicted of his murder and jailed for life in May 1992. It emerged at the trial that Andrew Browne had previously served with the Gordon Highlanders while Andrew Smith had served with the Devon & Dorset Regiment of the British Army. Browne was also given a second life-term for involvement in the murder of Liam McKee in Lisburn two months before Loughlin Maginn’s. [76] Apparently, Liam McKee was named in Brian Nelson’s files. [77]

NELSON’S CONVICTION

Nelson was given Army tuition in resisting interrogation at the outset of the Stevens Inquiry. It was only through his team’s investigative efforts that Stevens was able to identify and arrest Nelson in January 1990. Interviews revealed that Nelson had been in possession of an ‘intelligence dump’, crucial evidence that FRU handlers had seized and kept from Stevens for several months.

In 1992, Nelson was committed for trial on 34 charges – two of murdering Gerard Slane and Terence McDaid; four of conspiracy to murder, and 28 lesser charges. He eventually pleaded guilty to 20 charges on 21 January – 5 of conspiracy to murder; 11 counts of possession of documents likely to be useful to terrorists; 3 counts of collecting information; 14 of possessing information of use to terrorists and one of possession of firearms with intent. The prosecution dropped all other charges, including the two charges of murder. One charge of murder may have been reduced to conspiracy to murder. The authorities stressed that the DPP’s decision not to proceed was reached after ‘a scrupulous assessment of the possible evidential difficulties and a rigorous examination of the interests of justice.’[Emphasis added].[78] It is clear, however, that a plea bargain was agreed to prevent damaging information on FRU from emerging. Nelson received, merely, a ten year sentence. He was not charged with Pat Finucane’s murder.

De Silva’s report details the deceit, complicity and irregularities of the various security agencies – RUC SB, FRU and MI5. They all acted beyond the law, lying to their political masters, running propaganda campaigns, leaking massive amounts of sensitive information to loyalists, ignoring threats to the lives of those they were tasked to protect, telling falsehoods in criminal trials. [79] De Silva, however, exonerates British Government ministers.

During Nelson’s trial, the British authorities underlined repeatedly the fact that Stevens’ believed initially that the passing of information to paramilitaries was ‘neither widespread nor institutionalised.’ In 2012, De Silva wrote to Stevens to ascertain his current position. Stevens’ reply highlighted the withholding of documents. He wrote:

On the basis of all the intelligence gathered by all three inquiries, I do believe from these records that leaks of information from the security forces was far more widespread and extensive than expressed in my initial findings. [80]

With regard to the targeting of Pat Finucane, FRU claimed that Nelson was unaware of it.[81] While it was admitted that Nelson confirmed his home address, a story was fabricated that Nelson believed the target was Pat McGeown (a client of Finucane) because of his inclusion in a photo of Finucane provided by Nelson to the UDA. An undated MI5 report noted, however, that Nelson ‘undoubtedly did the recce on the solicitor, Patrick Finucane.’[82] Moreover, William Stobie, the man who provided the weapons for Finucane’s murder, was an RUC SB agent.

According to De Silva, key UDA suspects for Pat Finucane’s murder, L/20, L/28 and Ken Barrett were not investigated or arrested until the Stevens III investigation in 1999, more than 10 years after the murder. He noted that the failure of the RUC to ensure an adequate investigation was particularly significant ‘when considered alongside the wider inadequacy of the action taken against the west Belfast UDA prior to the murder and the decision by RUC SB to recruit Kenneth Barrett in 1991 after he admitted his involvement in the murder.’[83]

DOUGLAS HOGG

On 17 January 1989, Douglas Hogg MP, Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State at the Home Office, made a statement during a House of Commons Standing Committee debate on the Prevention of Terrorism (Temporary Provisions) Bill that was going through Parliament. He said:

I have to state as a fact, but with great regret, that there are in Northern Ireland a number of solicitors who are unduly sympathetic to Robinsthe IRA…I do believe it is true and I am stating it, on advice. It is something that the Committee should know…I am advised as a Minister that those are the facts. I believe them to be true and I state them as facts on advice that I have received. [84]

Prior to his statement in Parliament, Hogg had met with the RUC on 24 November 1988. Those in attendance at the meeting were Chief Constable Sir John Hermon, Senior Assistant Chief Constable Blair Wallace, the Assistant Chief Constable responsible for CID, ACC Monahan and Deputy Head of Special Branch, ACC Brian Fitzsimons. Hoggs’ Private Secretary took notes at that meeting which recorded that ‘the RUC referred to the difficulties caused by the half dozen or so solicitors who are effectively in the hands of terrorists’ and who made good use of their right to insist on access to documents.[85] Details of ‘family connections to PIRA’ of two solicitors, Oliver Kelly and Pat Finucane, were sent to Hogg subsequently.[86] Pat Finucane was murdered less than a month after Hogg’s intervention, on 12 February 1989.

De Silva was satisfied that Hogg’s comments in Parliament were made as a direct result of the briefing sent to him by RUC Special Branch. He reported that he did not believe the written briefing provided to the Minister substantiated the claims made by the RUC that solicitors such as Pat Finucane were ‘effectively in the hands of terrorists.’ [87]

The British Government has consistently refused to establish a public inquiry into the murder of Pat Finucane. In 2019, the UK Supreme Court declared that earlier investigations failed to meet standards required by Article 2 of the ECHR. Since then, Pat Finucane’s widow, Geraldine, has mounted a series of legal battles over the British Government’s response to those findings. In November 2020, former Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, Brandon Lewis, announced that there would be no public inquiry at that stage because he wanted police review procedures to run their course. He was ordered to pay £7,500 to Geraldine Finucane for the excessive delay in reaching that decision. A further challenge was taken regarding the legality of the decision to await the outcome of investigations by the PSNI’s Legacy Investigation Branch (LIB) and PONI. In December 2022, High Court Judge Scoffield ruled that the Government remained in breach of Article 2 and quashed the decision not to hold a public inquiry following ‘an unlawful failure’ to re-consider its position following the conclusion of a police review process. He ordered that a further £5,000 compensation be paid to Geraldine Finucane for the ‘culpable delay’ in Chris Heaton-Harris, the current Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, reaching a fresh conclusion. Heaton-Harris’ appeal was heard in September 2023 in which lawyers for the Government stressed that a public inquiry had not been ruled out and that Judge Scoffield had ‘gone too far.’ Fiona Doherty, KC for Geraldine Finucane, argued that its response had exacerbated the hold-up. Judgement was reserved.[88]

CORPORAL CAMERON HASTIE AND JOANNE GARVIN, UDR MEMBER

Cpl Cameron Hastie, 1 Royal Scots Dragoon Guards (1RS) and Private Joanne Garvin, UDR member, were convicted of being in possession of information likely to be of use to terrorists, in May 1989.[89] They were each given 18 months prison sentences suspended for two years. While Garvin was asked to resign from the UDR, the MoD made a decision to allow Hastie to continue to serve in the Army, which was very controversial, even within British Government Departments.

After the murder of Loughlin Maginn, there continued to be allegations of leaks of security forces’ information on IRA suspects – loss of material from Ballykinlar and RUC, Dunmurry, as well as material appearing in the press.[90] The Stevens’ Inquiry was continuing at that time.[91]

In a memo to the Attorney General dated 16 October 1989, DP Hill, NIO, noted that the BBC were claiming that Hastie’s original statement made clear that he was aware, when passing information to Garvin, that it might end up in the hands of loyalists. Apparently, a more serious charge of passing information rather than simply possession had been contemplated but was dropped in a ‘deal.’ The memo continued that, concerning Pte Garvin, the BBC claimed that her initial statements never made any secret of the fact that the information was expected to find its way to loyalist terrorists.[92] It was also noted that the possession of material likely to be of use to terrorists carried a maximum sentence of 10 years, while Hastie and Garvin received only 18 months suspended.[93]

Very soon afterwards, ‘papers derived from committal papers in the custody of the Clerk of Crown and Peace’ were made available to Ed Moloney, writing in the Sunday Tribune.[94] Hastie gave montages, names and addresses of IRA suspects to Garvin who passed them on to loyalists via a driver in a taxi firm she used regularly called Call-A-Cabs. The firm was owned by UVF member, Jackie Mahood. Her usual contact was another UVF man, Michael Taggart, whom she summoned to pick up the material. He was unavailable and, instead, a UDA member called Jackie Courtney came to pick it up. This meant that both loyalist organisations had access to it.[95]

In her initial statements, Garvin claimed that she had requested Hastie to make unauthorised checks on suspect car numbers on the British Army’s ‘Vengeful’ computer which held details of cars used by paramilitary suspects. According to Garvin, she did this a number of times using different soldiers and each time at the request of Taggart, who usually drove her to and from Girdwood Barracks in a Call-A-Cabs taxi.[96]

Hastie passed to Girvan a montage he claimed was given to him by a member of the Light Infantry in December 1987 when the Royal Scots took over from that regiment. It was claimed that the photographs with names and addresses were found as the Light Infantry solider was gathering his possessions prior to leaving Northern Ireland and Hastie gave them to Girvan in Girdwood.[97] She claimed that two other soldiers were giving material to the UVF in Tiger’s Bay or the UDA, in its Shankill Road office. Those soldiers, however, denied the claim and no charges were brought against them.

The initial statements made by Hastie and Girvan were not included in the final written statements of confession taken from the pair by the RUC, despite the fact that they could be interpreted as evidence to support a charge of conspiracy to murder, a much more serious offence than that of possession of documents.[98]

According to the original statements, the photographs and other information included details of IRA suspect, Adrian McDaid, whose brother, Terence, who had no links to paramilitaries, was shot dead on 10 May 1988. This was less than a month after the documents had been given to loyalists. Another Catholic, Patrick Fitzpatrick, from the Markets area of Belfast, was shot in the head outside a Belfast supermarket on 7 July 1988. He survived but lost an eye in the attack.[99]

Denis Taggart, brother of UVF member, Michael Taggart, a sergeant in the UDR was also alleged to be a member of the UVF. He was killed by the IRA in August 1986, which Garvin claimed had embittered her to the IRA.[100]

The NIO was furious about the retention of Hastie in the Army but the MoD was deaf to all entreaties. In an internal memo, BA Blackwell noted that the decision to retain him was ‘incredibly insensitive and morally wrong.’ Blackwell was dismayed at the way in which ‘a number of recent and forthcoming decisions which were MoD-led and often No. 10 sponsored’ had destroyed the effect of any modest confidence-building measures NIO had introduced in Northern Ireland.[101]

The British Ambassador, Nicholas Fenn, was no less upset at the decision. His telegram to NIO of the same date reported that the incident was widely seen in Ireland as ‘contempt for Irish sensitivities, further evidence that the Army is above the law and that Protestant terrorists are somehow respectable.’ He asked: ‘Would Cpl Hastie still be in the Army if the information in question had been useful to the IRA?’[102]

Cameron Hastie was indeed retained in the British Army and retired with the rank of Major!

ULSTER RESISTANCE

Recently declassified documents and PONI reports also shed fresh light on the activities of Ulster Resistance (UR). The signing of the Anglo-Irish Agreement in November 1985 led to uproar among the unionist community, in particular the Unionist parties. Just days before the first anniversary of the signing of the Agreement, Ulster Resistance was founded by the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) and Ulster Clubs (which included a number of DUP members, including David Trimble)[103] in opposition to it. The launch was chaired by DUP Press Officer Sammy Wilson and addressed by party colleagues Ian Paisley, Peter Robinson and Ivan Foster. A colour party wore paramilitary uniforms and maroon berets. The chairman of Ulster Clubs, Alan Wright, was also on the platform.[104] Over the following weeks, recruitment rallies were held in Kilkeel, County Down; Enniskillen, County Fermanagh; Larne and Ballymena, County Antrim; and Portadown, County Armagh. Ivan Foster told a newspaper reporter that UR had access to RUC intelligence and would use it to target and kill suspected members of the IRA.[105]

On 7 August, three months before the birth of UR, Peter Robinson, deputy leader of the DUP, led a loyalist mob of around 150 across the border into the village of Clontibret, County Monaghan. Although he was unmasked and unarmed, many of his accomplices wore masks and carried cudgels. The mob attacked two members of a Garda patrol and their police car was damaged. The convoy of more than 60 cars had set off from Tandragee, County Armagh and there was considerable evidence from RUC reports that their initial objective was to stage a march through the village of Keady because that route had been denied to the Apprentice Boys earlier that evening.[106] As that didn’t prove possible, due to security force presence, they continued on to Clontibret. The Gardaí were pre-warned by the RUC that loyalists were ‘roaming about in south Armagh and might seek to cross the border.’[107]

Robinson was the only one arrested as it was noted that he had ‘lingered’ while the others scarpered across the nearby border. Robinson claimed that the protest was a demonstration against the ability of Provisional IRA members to use the territory of the Republic as a safe haven. Among the charges brought against him were those of causing malicious damage and occasioning actual bodily harm.[108] He was described by Robert Stinson, an official in the British Embassy in Dublin, as ‘the hardest-liner among Unionist leaders’ and that ‘many suspect he has close links with loyalist paramilitaries.’[109] Two days after he was charged and out on bail, he claimed, at a loyalist rally in Portadown, that the British Government had offered a mercenary a five-figure sum to assassinate him.[110] An article in the Observer noted that Robinson had made some extreme comments – on one occasion he suggested that Margaret Thatcher should be electrocuted and, outside Belfast City Hall in April 1986, he declared that the only input he wanted to the Anglo-Irish Agreement was ‘a stick of gelignite to blow it away.’[111] Robinson’s trial in Dublin’s Special Criminal Court ended on 16 January 1987 when he pleaded guilty to the charge of unlawful assembly. All other charges against him were dropped. He was fined IR£15,000 and IR£2,588 for damage to cars and was ordered to keep the peace for 10 years.[112]

In December 1986, UR met with the UVF and UDA in County Armagh to discuss the acquisition of weapons. Quite a number of the membership of UR was also members of the UDA or UVF. It was claimed in the Sunday Tribune that at least two members of the DUP attended this meeting.[113] A BBC Spotlight programme in 2019 claimed that, in early 1987, senior UR member, Noel Little, using an alias, travelled to Geneva and Paris to meet a representative of South African arms company, Armscor. They named him as Douglas Bernhardt, an arms dealer of US nationality based in Geneva.[114] (It is possible that Millar’s agent in Zurich in 1985 and Bernhardt are one and the same person). Bernhardt was later arrested with Noel Little and two associates in Paris. It is claimed that the contact with South Africa came about through Alan Wright, leader of Ulster Clubs and founder member of UR. His uncle, Richard Wright, a native of Portadown, (another Armagh man working in South Africa) was an employee of Armscor. The deal was said to be arranged through Bernhardt, with whom Richard Wright had worked when the former had a Mayfair-based company in London. The relationship had endured and Bernhardt had become an agent for Armscor, scouring the world for up-to-date weaponry on behalf of his sanctions-strangled client. Peter Taylor claims that Bernhardt looked after the financial side of the 1987 arms deal.[115]

On 8 July 1987, the UDA, in collaboration with the UVF and UR, stole £325,000 from the Northern Bank, Portadown. Seven men carried out the raid. Three of the raiders wore police uniforms while the others were armed and masked.[116] Two men were later charged, at least one of whom had UDA connections, while only one man, Kenneth McDonald, was convicted. He was traced after leaving a forged RUC warrant card containing his photograph. He claimed he was paid £9,000 for his role in the raid.[117]

This stolen money was carried to Europe, mainly to Swiss bank accounts, by ‘respectable Ulster Protestants’ involved in banking, business and insurance.[118] It was used to purchase 206 Vz58 assault rifles, 94 Browning 9mm pistols, 4 RPG-7 rocket launchers and 62 warheads, 450 RGD-5 grenades, 30,000 rounds of ammunition. The consignment arrived in Belfast Docks from Lebanon in December 1987.[119] Douglas Bernhardt had arranged for the arms to be procured for a commission of £15,000 by a Lebanese arms dealer, Joseph Fawzi, who sourced the arms in Lebanon and Israel.[120] The full consignment was brought to James Mitchell’s farm (he of ‘Glenanne Gang’ notoriety) in County Armagh, where it was intended to be split three ways between the UDA, the UVF and UR.[121]

By 7 January 1988, police were aware that a large consignment of arms intended for loyalists had arrived in Northern Ireland. They also knew the identity of many of the senior paramilitary figures involved and witnessed a number of them meeting in Portadown on that evening. According to police intelligence obtained in 1990, by the time that meeting took place, Person D [Noel Little] had already taken possession of the UR share of the consignment.[122]

On the morning of 8 January Person E [Davy Payne]; Persons F and G [James McCullough and Thomas Aiken] drove three cars to a small carpark in Tandragee, County Armagh.[123] The two driven by McCullough and Aiken were hired maroon Ford Granadas while Payne was driving his own car. From the carpark they were led by Person C [identity unknown to the author] to Mitchell’s farm. Person C was driving an orange-coloured Chrysler Horizon.[124] They were said to have moved south-west on the B3 road from Tandragee. They were under surveillance by RUC members of E4A but they, inexplicably, ‘became unsighted’ of the three cars at that point.[125] At the farm, they loaded the UDA’s share of the consignment into the two hired cars and made their way towards Portadown with Payne driving ahead of them. James Mitchell and at least six other men were present during the loading of the weapons. Shortly before midday, E4A[126] allegedly picked up the scent again and noted the cars travelling north on the A27 road towards Portadown.[127]

At noon, the RUC’s HMSU[128], attached to Special Branch, set up a VCP at Mahon Road, outside the British Army barracks in Portadown. As a result, the cars were stopped and a very large cache of weapons was recovered. The first car was Davy Payne’s which did not contain any weapons. The boots of the other two cars, the Granadas, were filled to capacity with rifles and boxes. The first of the two contained 36 Vz58 rifles and 150 grenades while the second contained 25 Vz58s, 124 rifle magazines, 11,520 rounds of 7.62 ammunition and 30 Browning pistols. The drivers of the cars were James McCullough (55) a lorry driver from Bangor and Thomas Aiken (31) unemployed, from Forthriver Park, Belfast.[129]

PONI describes some of James Mitchell’s previous activities. It was established that his farm was under surveillance during the 1970s and during that period he was alleged to have assisted the ‘Glenanne Gang’ in so far as he allowed his farm to be used for ‘related preparatory acts.’ PONI notes that Mitchell was directly implicated in terrorism by police officers, who were themselves accused of serious crime. When he was arrested in December 1978, Mitchell described his farm as one of the main UVF arms dumps for mid-Ulster loyalists. He received three one-year prison sentences on 30 June 1980, each of them suspended for two years. Again, in late 1983, Mitchell was connected, by police intelligence, to the storage of firearms on behalf of the UVF.[130]

Within a week of the arrests at Mahon Road, Portadown, police were aware that a number of men, including Mitchell, had met at a house in Markethill, to discuss the arms seizure. The PONI considered it noteworthy that Person D [Noel Little] lived in Markethill.[131]

It was claimed that the Detective Chief Superintendent in charge of CID in the RUC’s South Region and the Detective Superintendent responsible for Portadown/Armagh area joined detectives in the Markethill area with a view to locating the farm where the weapons had been stored. They failed to find it on 12th and again on 13 January 1988.[132]

Information was received by police in 1988 that, within two hours of the arrests of Payne and his associates, the remaining firearms were removed to another location in a farm vehicle. Mitchell had received a ‘tip-off’ that police intended to search his farm so he drove the remaining weapons to a safe location in Markethill.[133]

The PONI also discovered an entry in a RUC Occurrences, Reports and Complaints Book from Markethill RUC Station dated 9 January 1988, which stated:

4pm. Derelict house search: Between 2.10pm and 3.55pm a search team from Royal Engineers carried out a house search at Lough Road, Glenanne. These premises are owned by James Mitchell. John Mitchell [brother of James] supplied the key for rear door. No damage was done and nothing found – key returned.[134]

Incredibly, intelligence records indicate that the RUC searched Mitchell’s farm again, three years later, on 21 January 1991 and recovered 173 rounds of .303 ammunition and 49 rounds of .455 ammunition, from the grounds of the property. No person was charged in relation to this seizure and the PONI investigation found no evidence that Mitchell was subject to enquiries by the police in relation to his role in the storing of the imported arms.[135]

Intelligence received in 1990 reported that the notorious Robin Jackson, leader of the mid-Ulster UVF, had possession of some of the weapons from Mitchell’s farm, including 10 Vz58 rifles, ammunition and one RPG launcher. He distributed two of the rifles and the RPG launcher to Person Y, the ‘Brigadier’ of East Belfast UVF. This supports intelligence from February 1989 that Lurgan UVF had a large number of weapons in a ‘deep hide’ under the control of Robin Jackson.[136]

When the case came to trial, Payne and McCullough pleaded guilty to possessing the massive arms haul of guns and grenades. Aiken denied the charges and was sent for trial. At the end of his trial in which Aiken was found guilty, Payne was sentenced to 19 years’ imprisonment while McCullough and Aiken were each jailed for 14 years.[137]

On 4 February 1988, a haul of weapons was seized by the RUC at Flush Road, Ballyutoag on the outskirts of north Belfast. Police believed that they were awaiting distribution to various UVF battalions in the city. A man from Bangor was arrested. The haul included 38 Vz58 assault rifles, 15 Browning pistols, 100 grenades. This was believed to represent about two-thirds of the UVF’s share of the consignment.[138] According to PONI, also seized were 30,030 rounds of 9mm ammunition, 10,730 rounds of 7.63mm ammunition, one RPG-7 rocket launcher, 26 RPG-7 rockets. A further search located two more Browning pistols and 250 rounds ammunition.[139]

In the weeks following the Mahon Road seizure, Persons C and D [Noel Little] were arrested but denied all knowledge of the arms importation and were released without charge. The arrest of Person D [Little] appears to have been linked to his telephone number having being found on Person G [McCullough]. The arrest of Person C arose from a search of the home of Person D [Little] where documents implicating Person C were recovered.[140]

PONI referred to de Silva’s commentary on a senior police officer where he stated that, in the mid-1980s, the Security Service (MI5) received intelligence that an unnamed and potentially very senior RUC officer might be assisting [loyalist] paramilitaries to procure arms. FRU and Security Service reports from 1987-9 also suggested that ‘a small number of senior police, Army and UDR officers may have been providing assistance to loyalists’.[141]

PONI is very critical of the failure to share intelligence with the police investigators and, particularly, the failure of Police Officer 16 to consider Mitchell’s farm as a potential location. She noted that he had previously participated in investigations in which Mitchell’s farm had been identified as a location where the UVF stored arms. Despite being implicated by intelligence in the importation of weapons, senior members of the UVF, UDA and UR were not the subjects of police investigation. PONI stated that, in a separate public statement, her predecessor, Dr. Michael Maguire, had established that the individuals responsible for the weapons’ importation, which were later used in at least 80 murders, were never subjected to police investigation.[142] He had also identified intelligence gaps and failings in the January 1988 surveillance operation.[143] This, Marie Anderson asserts, can be attributed to a decision by Special Branch not to disseminate the intelligence implicating those individuals. She describes this as ‘indefensible.’[144]

UR encapsulates the porousness of the boundaries between unionist politicians, loyalist paramilitaries and locally-recruited security forces, which is so evident in the arms importation saga. It is also fascinating to observe the adroitness with which unionist politicians can, at one moment, be so clearly connected to loyalist paramilitaries and, in the next, to shrug off this connection as if it never existed. It is, however, a matter of historical record that the DUP had a militant wing, however short-lived.

It is remarkable that the location chosen for the storage of this massive consignment of weapons was the farm of James Mitchell in Ballylane, Glenanne, County Armagh. The choice illustrates and reinforces the centrality of this farm to the activities of loyalist paramilitaries. Its importance continued right from the beginning of the conflict through to the 1990s. Mitchell was clearly a trusted figure in unionist and loyalist circles and indispensable to loyalists in mid-Ulster and further afield. It is also noteworthy that the infamous Robin Jackson emerges as a player in this affair.

In the 1970s, it was from Mitchell’s farm that members of the mid-Ulster UVF, along with security force associates, set out on murder expeditions all around the Murder Triangle area and across the border to counties Louth, Monaghan and Dublin.[145] It was a place where British soldiers on tours of duty could get a comforting cup of tea; where drilling by UVF members took place; where sectarian murders were planned; where explosives were mixed; where plans of the layout of pubs sat in the kitchen window; where home-made weapons were tested and where arms were stored. It was a haven and a critical resource for loyalists, a depot and a base. In the late 1980s, it was needed again to store the largest weapons haul of all. Mitchell himself had been a member of the B-Specials and from September 1974 until July 1977, served as a member of the RUC Reserve. He seems to have been untouchable. When circumstances conspired to bring him, at last, before the courts, he was given a suspended sentence. At all other times, he escaped without any charges being brought against him. Although PONI believes that the members of the RUC’s E4A, genuinely ‘became unsighted’ of the cars making their way from Tandragee to Mitchell’s, one has to be sceptical of this. Mitchell not only allowed his farm to be used for ‘related preparatory acts’ as PONI suggests, but he facilitated murder on a large scale.

SOME MURDERS WHERE THE IMPORTED WEAPONS WERE USED

It was noted above that the imported weapons were used in more than 80 murders. The first recorded use of a Vz58 assault rifle was the attempted murder of a Mr Burns in north Belfast in March 1988. The same weapon was used to murder Seamus Morris and Peter Dolan, also in north Belfast, in August 1988.[146] Vz58 rifles were used in multiple murders – five were killed at Sean Graham’s Bookmakers, Belfast; eight at the Rising Sun Bar, Greysteel, County Derry; and six at the Height’s Bar, Loughinisland, County Down. On 16 March 1988, one of the weapons used in the murders of Thomas McErlean, John Murray and Caoimhín MacBrádaigh in Milltown Cemetery by Michael Stone, was a 9mm Browning pistol, part of the imported consignment. He also exploded grenades which came from the haul.[147] Incredibly, PONI’s research led to the discovery of the Vz58 used in Graham’s Bookmakers in the Imperial War Museum (IWM), London, as well as a Browning pistol used in the same atrocity which had been stolen from Malone Road UDR armoury on 31 January 1989.[148] It emerged that discussions between the IWM and the RUC had begun within weeks of the attack, although the rifle wasn’t donated to the IWM until 1995.[149]